Atanas Stoyanov

Nowadays there are numerous policies at local, national and international level, aiming at improving the situation of the largest ethnic minority of Europe: the Roma people. According to the European Union and its European Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies ‘Many of the estimated 10-12 million Roma in Europe face prejudice, intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion in their daily lives. They are marginalized and live in very poor socioeconomic conditions’ (European Commission 2012). This current European Roma Strategy (called further in the text the Framework) is the highest political commitment towards the Roma in history that was transposed in 27 out of the 28 EU-member states. (Questions and Answers – European Commission 2013). The Framework adoption per se was the result of years of struggle for recognition. Various nongovernmental organizations from across Europe, including the Open Society Foundations of George Soros (Open Society Foundations 2015), fought constantly to bring the Roma issue high in the political agenda. A struggle to make the daily problems that the largest European ethnicity face are visible for all and a target of a special policy treatment. Yet, in this paper I will not focus on defining or judging various concrete polices as a failure or as a success. Instead, using the method of critical discourse analysis (van Dijk 1994), I will firstly conceptualize the widely used notion of “Roma policy”, since there is still no clear definition of the collocation. Secondly, I will shortly compare the definitions of “Roma” given by the Council of Europe and the European Union and I will analyze “Roma” as EUs target from a public policy perspective. Moreover, I will look at how the EU technocrats can influence the definition of “Roma”. In the end I will present my conclusions on whether Roma people are being seen by the EU as an ethnicity or as a socio-economic category and I will provide some recommendations particularly towards the European Council and the Commission.

WHAT DOES A “ROMA POLICY” MEAN?

A Google search for the “Roma policies” collocation will provide us with 5,240 results. The frequency of usage of “Roma policy” is even higher: around 17,000 results. One can even open the web page of the “European Roma Policy Coalition” (Romapolicy.eu 2015). However, there is no clear definition of what exactly a “Roma policy” is. In contrast to ordinary sectorial policies such as “healthcare”, “education”, “agriculture”, etc. the collocation of “Roma policy” is quite extraordinary. Roma policies, in practice, can be seen as an aspect or as a subcategory of any other policy besides the policies targeting other ethnicities. Thus, I will further investigate the meaning of the word “Roma”.

According to the Romani language, as cited by the Council of Europe’s Descriptive Glossary of terms relating to Roma issues, “Rom” means “man of the Roma ethnic group” or “husband”, depending on the variant of Romani”(Council Of Europe Descriptive Glossary Of Terms Relating To Roma Issues 2012). The official definition provided to be used in every document issued by the Council of Europe since 2012 up to date is: “The term ‘Roma’ used at the Council of Europe refers to Roma, Sinti, Kale and related groups in Europe, including Travellers and the Eastern groups (Dom and Lom), and covers the wide diversity of the groups concerned, including persons who identify themselves as Gypsies”. After 2010 the terms “Gypsi” and “Gypsy” are not anymore used by the Council of Europe since they are considered to be pejorative. Few main conclusions should be made here. The first and the most important is that “Roma” is the international ethnonym [1] used to name the people who define themselves as Roma in their own language. The second is that even those people might not speak Romanes/Romani (the Roma language) they share the same historical roots and they self-define as Roma or by the given exonym [2] in the respective country, i.e. “Roma” is being defined as a heterogeneous ethnicity, which shares the same historical origin.

Based on this, “Roma policies” can be defined as all those policies aiming at the members of the Roma ethnicity, as individuals and as a collective. The term “Roma” can be explicitly mentioned in the policy title, such as in the “National Roma Integration Strategy” for example. In other cases “Roma” can be one of the potential targets/beneficiary group of a certain policy as well, but not explicitly mentioned in the document title. Such is the example of the National Plan for Employment of Bulgaria 2015 where “Roma” is listed as one of the target groups. For example, „the need of measures, directed specially to the youngsters without education and skills, including the Roma” or “better addressing the most vulnerable, such as low-skilled and older workers, long term unemployed and Roma” (National Action Plan For Employment 2015). It is apparent that the Roma people as a category share some common problems with the society that need to be solved and therefore there are so many documents mentioning or targeting Roma. In targeting Roma, it is also apparent the negative context in which they are being mentioned. In hundreds of documents, articles and even civil society reports, Roma fall between categories such as “people with disabilities”, “low skilled” and “other vulnerable groups, including Roma”. And while one can clearly state that the problems of people with disabilities occur because of their disability, the problems of the “law skilled” is the lack of skills etc., it should be also clearly stated that the problems of Roma occur because of their ethnicity, i.e. the discrimination based on their ethnic and cultural difference.

THE “ROMA” AS A POLICY TARGET OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

Before analyzing why only Roma among many other ethnic minorities in Europe should have a special policy treatment, I will look at the definition of “Roma” given by the European Union.

Comparing the Council of Europe and EU, the latter certainly has more instruments to transpose its legislation into the national one and to directly affect the European citizens, including the estimated 6 million Roma living in the EU (Fra.europa.eu 2015). The first footnote given in the Framework, in the very first sentence of it, attempts at providing us with definition of what does “Roma” mean:

/Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Europena Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions: An EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020 COM (2011) 173 final, page 2/

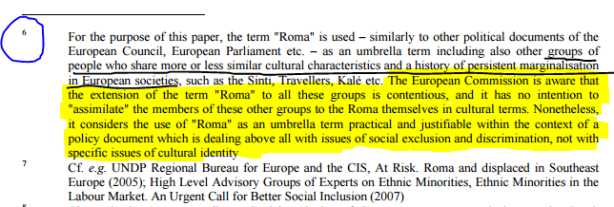

Besides that it is not clear why the footnote was inserted after the number /10-12 million/and not after the term “Roma”, this leads us to look at the bottom of the page where with a small print is stated: “[1] The term “Roma” is used – similarly to other political documents of the European Parliament and the European Council – as an umbrella which includes groups of people who have more or less similar cultural characteristics, such as Sinti, Travellers, Kalé, Gens du voyage, etc. whether sedentary or not; around 80% of Roma are estimated to be sedentary (SEC(2010)400)” (European Commission 2012).

The first element that is being emphasized in this definition is not the definition per se but the fact that what is following as a definition was used in other EU-documents. It is debatable what exactly the function of this preface is and whether it should be there at all, since it does not serve the general purpose of the footnote: to explain what does the EU mean by “Roma”. Then “Roma” is being defined as a generic, “umbrella” term that includes groups who share “more or less similar cultural characteristics”. What this should mean?

According to the Oxford advanced learner’s dictionary the meaning of “culture” in the English language is “the customs and beliefs, art, way of life and social organization of a particular country or group” (Oxforddictionaries.com 2015). This EU definition misses to exclusively define Roma as an ethnic group, although the linkage with “such as Sinti, Travellers, Kalé and Gens du voyage”, four specifically mentioned ethnonyms, states it indirectly. Hardly anyone who has not heard before of these ethnic groups (some of which defined in the CoE terminology) will understand that it comes to groups of people sharing common ethnic origin. One can also argue why these four groups, all from Western Europe and comparatively smaller in numbers, are being specifically mentioned but groups such as “Kalderashi”, “Horahane Roma”, “Yerlii” or any other are omitted (Popov and Marushiakova). Back to the text analysis, the following short but pointedly “etc. whether sedentary or not” tells us, firstly, that there is a list of such groups, which is obviously not in the text and there is no reference where it can be found. Secondly, “sedentary or not” comes to tell us that nomadism is a crucial characteristics of all Roma. Finally, there is a statement from which it can be inferred that 20 % of Roma, or only 1/5 of them, are not sedentary. The conclusion, which can be derived from this final part of the text is that the European Union connects categories “migration” and “Roma”. In the end of the footnote we find the classificatory code of another EU document: “SEC (2010)400”. This appears to be the “Commission staff working document: Roma in Europe: The Implementation of European Union Instruments and Policies for Roma Inclusion – Progress Report 2008-2010” issued on April 2010. There is presented a very similar to the abovementioned, but more detailed definition of “Roma” again under a footnote [6]:

/Commission staff working document: Roma in Europe: The Implementation of European Union Instruments and Policies for Roma Inclusion – Progress Report 2008-2010, p. 3, SEC (2010)400/

In this definition, besides the common cultural characteristics, there is added that European Roma share a “history of persistent marginalization”. Moreover, the EU declares that it is debatable whether to put all these groups under the umbrella of “Roma”. However, it is stated that using “Roma” for the purposes of a public policy documents is justified because “Roma policy“ is such “which is dealing above all with issues of social exclusion and discrimination, not with specific issues of cultural identity”. In other words the meaning of “Roma”, here in the EU definition, makes a significant shift from issues related to ethnicity, cultural identity, language and history (which is closer to the definition of the Council of Europe) towards the what EU calls more “practical” usage of the ethnonym “Roma” as an umbrella term for all who share the socio-economic exclusion and suffer of discrimination.

European technocrats can hardly realize what an ethical crime is to distort the meaning of the Roma-ethnonym used for centuries by the millions of Roma people in their own language to name themselves (in Romanes “Roma” means “human beings, people”) by turning it into a synonymous of socio-economically disadvantaged and discriminated generic category of people. This is a cultural ignorance which without any reasons turns the traditional usage of the notion and is leading to the formation of a new, modern, public policy usage of the term “Roma”. By framing the issue in a “practical” key, EU institutions do not only hinder the inclusion of the disadvantaged Roma, but they further reinforce the negative stereotypes about them. Moreover, such generalization stigmatizes hundreds of thousands of middle class and rich Roma. According to the EU definition, do poor and marginalized Roma should stop calling themselves Roma once their livelihood reaches the level of the middle class in the respective country? Unexplained remains also why, after writing numerous pages strategies for Roma and spending significant amounts of national and European funding, their definition is hidden in a maze of references and footnotes, instead of being the most visible and clear part of such strategies.

ARE THE “ROMA” POLICIES SOUND?

Relying on the public policy theory, I will use the classical concept of the policy cycle (Akrofi 2015) introduced by Lasswell (1956) to analyze if the European Roma policies, and precisely the Framework, are theoretically sound and conceptualized. The policy cycle, with several slight updates through the years, still remains the most useful and practical tool for policy makers to design or asses a given public policy. The steps that are being followed in the policy cycle are five: problem identification/agenda setting, policy formulation, adoption, implementation and assessment. The correct identification of the Roma problem in this sense is crucial for all the consequent policy cycle stages. Due to the word limitation of this paper, I will limit the Framework analysis only within this first stage. At this point policy makers describe and define the existing problems in an objective and well informed manner. They define clearly who are the ones affected by the given policy and who are the ultimate target of the introduced policy through a developed set of criteria for the target identification. Thus, when everything is being set in a clear and unambiguous language, it can be presupposed that the state machinery and all the related institutions will have no difficulties during the policy implementation.

In the previous chapter I argued that the definition given to “Roma” is not very clear and that the notion of the largest ethnic minority of Europe is being changed for a “generic group of socio-economically disadvantaged people” where the list finishes with “etcetera”.

If we assume that Roma are an ethnic group we can see that the Framework does not address any Roma need related to language, culture or history. To be concrete, the words “culture” and “history” are totally missing and the word “language” is being used only once in the collocation “language and literacy”.

Even if, for a moment, someone assumes that Roma are all those who share the same socio-economic disadvantaged position in society, it is still not clear who the ultimate beneficiaries of this public policy are or even who the Roma are. There is no given effective mechanism and criteria for the determination of the policy target. Are these only people below the level of poverty? Do they have to belong to an ethnic minority? What if someone is discriminated in terms of equal access to housing or employment but this someone does not define as Roma? These questions remain unanswered. There is no unambiguous data for the number of Roma in the different European countries and in many countries Roma are not even recognized as a national minority. How the Framework and the related National Roma integration strategies are expected to work without these simple policy pre-conditions for success?

Further, what are considered to be Roma’s problems as they are defined in the Framework? The document states, in different parts of the text, that these are economic and social marginalization, discrimination, equal access to fundamental rights and poverty. Briefly, all these boil down to ethnic discrimination because of cultural differences and consequent cultural ignorance and unacceptance. These remind the commitment of the EU Roma policies that they will deal with “issues of social exclusion and discrimination” (European Commission 2012). However, when it comes to setting up the policy priorities, among the four main areas of “Roma integration”, namely access to education, employment, healthcare and housing, [3] discrimination is not even mentioned . In other words, this is a policy that treats some effects of the discrimination such as the higher unemployment among Roma, the comparatively worsen access to healthcare and housing conditions or lower quality of education, but not the causes of the problems. Therefore, because of the various violations of the policy formulation, it can be concluded and predicted that the Framework and other related policies will have no real effect on the improvement of the Roma, regardless the distinction between “socio-economic” or “ethnic” category.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It became clear that the concept of “Roma” used by the European Union in all its related documents and particularly in the Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies, is to a greater extend devoid of ethnic dimensions. The clear definition of the “Roma” is missing, confusing and footnoted, and “Roma” is used as a byword for all the groups of people who are in disadvantaged socio-economic position. This not only does not help ethnic Roma, but turns the ethnonym “Roma” into a negative term and presupposes that ethnic Roma cannot be part of the middle class. The text of the Framework predisposes Roma, who are well placed in society to be ashamed of their ethnic origin and to be assimilated. The language, culture and history of Roma are being disregarded by the European Union and their discrimination and stigma remain without effective policy respond.

A key recommendation towards the European Council and the Commission is to abandon the current policy of cultural ignorance towards the Roma and to focus on making the Roma culture, language and history equal to all other national cultures and languages. There are many signs of hope that EU policies towards Roma may change for the better. One positive ray of optimism was caused by the decision of Open Society Foundations and the Council of Europe from late March, 2015, to settle a European Roma Institute which would compensate for all the years of neglecting the Roma culture (2015). This might be a great example for EU. Another source of hope, is that in the day of writing these lines, the European Parliament is voting the Resolution on the occasion of International Roma Day – anti-Gypsyism in Europe and EU recognition of the memorial day of the Roma genocide during World War II (2015/2615(RSP)) [4] . Although this resolution was already rejected twice by various European political parties, the plight of the Roma NGOs for cultural and historical recognition still continues.

FOOTNOTES

[1] the name applied to a given ethnic group

[2] where the name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people

[3] Page 4 of the EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies

[4] The author personally participated in a special meeting with MEPs in March 2015 to discuss the future voting of the document.

REFERENCES

2015. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/learner/culture.

2015. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/why-we-are-setting-european-romainstitute.

Council of Europe Descriptive Glossary of Terms Relating to Roma Issues. 2012. Council of Europe.

European Commission, 2015. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: An EU Framework For National Roma Integration Strategies Up To 2020 COM (2011) 173 Final. Brussels: European Commission.

Fra.europa.eu. 2015. ‘Roma | European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights’. http://fra.europa.eu/en/theme/roma.

Institution, Using. 2015. ‘Using The Policy Cycle As A Format; Describe The Policy Process In Your Country Or Institution’. Academia.Edu.http://www.academia.edu/1207664/Using_the_Policy_Cycle_as_a_Format_Describe_the_Policy_Process_in_your_Country_or_Institution.

National Action Plan for Employment. 2015. Sofia: Republic of Bulgaria.

Open Society Foundations, 2015. ‘The Roma and Open Society’. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/roma-and-open-society.

Popov, Veselin, and Elena Marushiakova. ‘A Contemporary Picture of Romani Communities in Eastern Europa’. Lecture, Council of Europe.

Questions and Answers – European Commission. 2013. Brussels: European Commission, DG Justice. http://ec.europa.eu/justice/newsroom/contracts/files/2014s140- 250468/questions_answers.pdf.

Romapolicy.eu, 2015. ‘About | European Roma Policy Coalition (ERPC)’. http://romapolicy.eu/about/.

Van Dijk, T. A. 1994. ‘Critical Discourse Analysis’. Discourse & Society 5 (4): 435-436.

Doi: 10.1177/0957926594005004001.

Atanas Stoyanov

Atanas Stoyanov